He is the nephew of reputed Dayton gangster William “Bill” Elias Stepp.

Buhrman was facing lethal injection if convicted in Greene County on original charges of aggravated murder with death specifications in the Feb. 23, 1983, homicides of Patti L. Stanley, 22, of New Carlisle; Jon C. Stroop, 32, of Kettering; and Daniel E. Wilson, 30, who lived at a rented farmhouse at 2431 Indian Ripple Road in Beavercreek Twp. He also faced 15 years to life if convicted of aggravated cocaine trafficking in Montgomery County.

History of the case

The bodies of Stanley, Stroop and Wilson were discovered Feb. 24, 1983, by Wilson’s mother and sister at Wilson’s rented farmhouse. They were within 10 feet of each other in a living room at the front of the house.

The victims were shot with at least two guns and died of gunshot wounds and lacerations. No time of death was determined at autopsy, but none of the victims were seen alive after 8 p.m. the night before. Police described the deaths as a drug-related crime and said Wilson had been involved in drug dealing. Officers found about two grams of cocaine at the scene, according to Journal Herald and Dayton Daily News archives.

Police did not have any strong leads on who was responsible for the triple homicide until April 1987, when police arrested Steve Mountjoy on unrelated charges.

In 1989, Mountjoy, who authorities said was at the scene but was granted immunity in the case, identified Buhrman as the third man involved in the homicides.

The triggerman was identified as James E. Stelts. He pleaded no contest in 1991 to murder and was sentenced to 15 years to life. He is incarcerated at the London Correctional Institution, according to Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction records, and is eligible for parole next year.

Mountjoy was placed under the federal witness protection program and was imprisoned until 1997 for other crimes.

‘Incomprehensible’ death scene

Mountjoy told authorities that Buhrman was owed money by Wilson and that he accompanied him and Stelts to Wilson’s Indian Ripple Road farmhouse in what he thought was a plan to steal money and drugs.

In court records, authorities called the gruesome aftermath of the triple homicide an “incomprehensible,” execution-style death scene.

Buhrman remained outside as Mountjoy and Stelts, who was screwing a suppressor onto his .22-caliber Ruger, walked up to the farmhouse.

Posing as police, Mountjoy said, they drew guns and acted like it was a drug bust. But as Wilson opened the door, Mountjoy said Stelts “started blasting.”

Stanley, who was six weeks pregnant and Stroop’s girlfriend, escaped but was caught. After bringing her back into the house, Mountjoy said Stelts “puts the gun to the girl’s head and says ‘Sweet dreams, baby,’ and then blasted her (twice) in the head.”

They then spent the next five minutes ransacking the house, finding $35,000 to $40,000 in cash and a little more than a kilogram of cocaine, Mountjoy told authorities, according to newspaper archives.

As they were leaving, they noticed that Stanley was still alive, gasping for air. Stelts then took out a knife, pulled her head back and slit her throat. He then also slit the throats of the other victims and smashed a fish bowl full of coins over one of the men’s faces. Police said following the deaths there was glass and coins all over the floor of the bloody crime scene.

Jailhouse interview

In late 1990, now-retired Dayton Daily News courts and crime reporter Wes Hills recorded a two-hour interview with Buhrman, in the custody of ODRC.

During the interview, Buhrman described his life growing up, including a traumatic experience involving “Uncle Bill,” the reputed gangster, his impressions of Stepp, what led to the triple homicides and the fallout.

Buhrman graduated in 1974 from Kettering’s Fairmont East High School, where he described himself as a “C” student, and said that he worked 30 hours a week all through high school with jobs at various times at a former Gold Circle and a gas station.

He had never been in trouble except for one time as a teen when a friend he was with took down a mailbox and they were caught.

His first solid memory of Stepp was around 9- or 10-years-old during a family reunion at a farm near Russellville in southern Ohio.

“There was a little beagle dog and I made friends with the little puppy dog,” he said. “Bill took the dog and killed it in front of me because it was raiding the chicken coop. He shot it. … I was traumatized as a child. I cried."

He described Stepp as a larger than life figure.

“He was like a god in the family. Everybody worshiped him and looked up to him,” Buhrman said.

Stepp was ambidextrous with long arms and was a naturally strong, good fighter. Buhrman grew up hearing stories that Stepp’s father used to take him to the docks as a teen in Cincinnati and bet on him to fight grown men.

“He has an ungodly adrenaline surge so when he gets mad he gets strong as 10 men,” he said.

His uncle made money mostly doing cons but also through burglaries, robberies and other thefts.

He and his cousins were proud to tell their classmates they were related to Stepp, and Buhrman spent years during the 1960s on the receiving end of lectures and coaching of the con game by the old-timers.

“I was in awe as a young man and today I look back and it’s frightening and sickening really,” he said.

Growing up, Stepp’s brother, Ernie, whom Buhrman described as “a very violent person,” would stay at his house for months at a time because of a tumultuous relationship with his wife. “Bill used him and manipulated him a lot. They would go out and make all kinds of money and Bill would keep it all and give him pennies. He was always bitter and angry about it.”

Buhrman said he had always been interested in cars and had a strong worth ethic.

“My entire life I’ve always worked,” he said.

Once he graduated and was working full-time, on the side he would buy cars, do some minor fixes and sell them through trade posts and auctions until in 1978 he was ready to deal in cars exclusively.

“I went into the car business for myself. I saved up $8,000 legally,” he said. “I made about $60,000 my first year in the car business.”

He started getting involved with Stepp around 1976, ’77, going around to dog fights and would raise puppies for his uncle.

As he continued to do well in his used car businesses, Stepp insisted on getting a cut, even when the business was legitimate and Buhrman was “doing all the work.”

Setting stage for murder

A former Fairmont East classmate involved in cocaine trafficking reached out to Buhrman to see if he could get his uncle’s assistance. He said that Wilson — a man unknown to Buhrman — owed him money and had been using Stepp’s name when making threats toward him.

It took a few weeks to materialize, but Buhrman said there was a plan “to rip off Wilson” for using Stepp’s name that would involve breaking in and taking money and other stuff to “put him out of business.”

Stepp and Stents had spoken about the plan and Buhrman said that he initially was not going to be directly involved.

On Feb. 23, 1983, after Buhrman had returned from a car auction, he got a call telling him “tonight,” regarding the break-in at Wilson’s farmhouse.

One of the people who was supposed to be involved was in Columbus, too far to make it in time, so Buhrman said he stepped in to be the driver to drop off Stents, Mountjoy and a third man, but that the other man ended up as the driver who took them to a wooded area near the farmhouse.

Buhrman said he had never done a burglary before, but did think it was odd that Stents had at least three or four guns and knives.

When they got closer, he said the house had lights on with cars in front. He thought it was a bust and they needed to wait for them to leave. However, after waiting for a while, Stents and Mountjoy approach while Buhrman, who was unarmed, stayed put.

“I didn’t understand why they were doing what they were doing,” he said.

He did not hear anything, but saw Stanley come out and get taken back inside.

Buhrman then approached the house. He stepped to the door frame and stopped, he said.

When he looked to his right he saw Wilson on his back on the couch, obviously deceased. He says he was told Mountjoy shot Wilson but did not witness the shooting.

Stents had Stanley on her knees in the middle of the floor, the gun at the back of her head when he shot her before they started ransacking the house.

He said Mountjoy was the one who smashed the glass filled with coins over one of the men’s face and head.

After the slaying, the trio got in one of the vehicles at the house and drove to a nearby shopping plaza before they made it back to Buhrman’s house in Miamisburg.

Buhrman said he did not know whether Stepp authorized the slayings, whether the men acted on their own nor whether his uncle intended him to be involved. However, one thing he knew for certain is that Stepp called the shots.

“I lived in fear 24 hours a day,” he said, fearing he would be killed to keep quiet.

Stepp died of natural causes at age 73 in 2008.

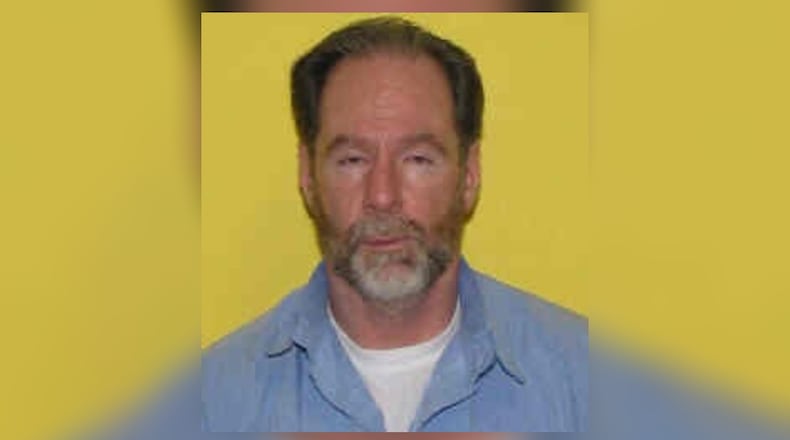

Credit: Ohio Department of Rehabilitation & Correction

Credit: Ohio Department of Rehabilitation & Correction

About the Author